We all know that obesity is harmful, and that weight-loss is difficult. This is frustrating for GPs and for our patients. However, I believe this could be avoided easily (because most doctors still manage obesity based on opinion rather than on evidence)…

Just have a look at the following easy-to-read summary of the key studies. While I don’t expect to fully change your mind, I hope to challenge your thinking and to offer you an interesting read. Let’s start…

Note: some of the following ideas were published previously in my review of obesity management guidelines1 and in my articles in the Lancet2 and NEJM3,4. In April 2024 I had the honor to present this topic as a keynote at the European Young Family Doctors’ Movement:

1. Why is obesity management frustrating? Because we ignore the evidence.

My approach to this article is simple. I tried to answer the most relevant clinical questions with the best available research evidence. While there are thousands of studies on obesity, here I tried to select – if available – only the most robust study designs:

- Systematic reviews rather than single studies (to avoid ‘cherry picking’).

- Intervention studies rather than observational studies (to assess causality).

- Long-term studies rather than short-term studies (to be more relevant).

- Clinical outcomes rather than intermediate outcomes (to be more relevant).

In other words, instead of citing some studies which confirm what I already believe, I just show you the key studies (all of them; if I missed any, please send me an email). Importantly, the results of these studies clearly indicate that our usual obesity managing is wrong…

2. What causes obesity? Not what common knowledge tells us.

Is obesity caused by lack of willpower (or even lack of intelligence)?

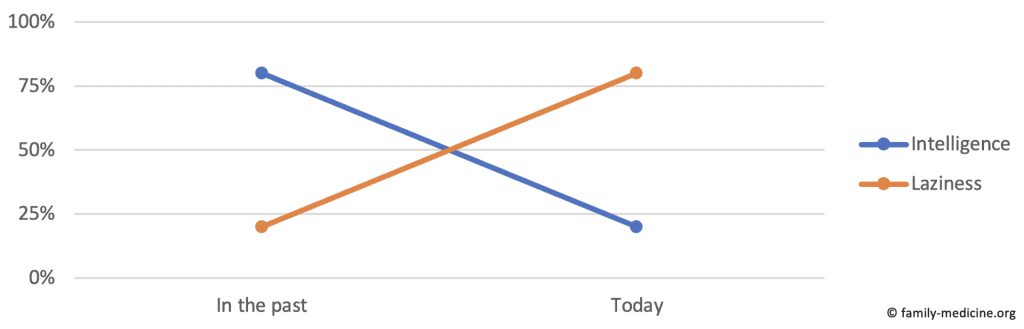

To be honest, I know that many (most?) of my medical colleagues believe this causes the rise of obesity:

It’s almost certain that lack of intelligence cannot explain the rise of obesity. Why not? Have a look at the following graph which shows that intelligence increased quite a lot in the last century, which is called the “Flynn Effect”:

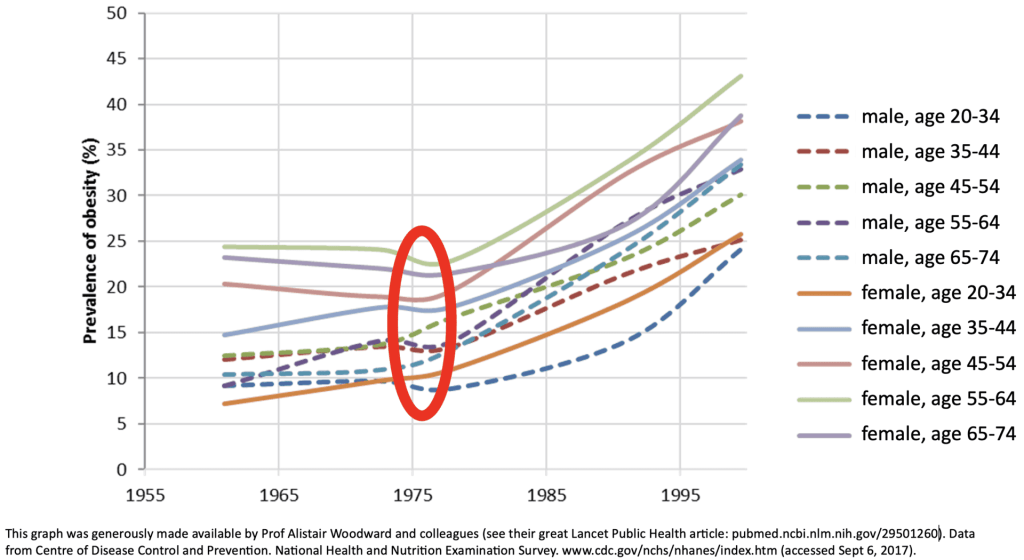

Can willpower explain the rise of obesity? No. Why not? Just look at the following graph, and ask yourself:

- How could willpower explain the sudden rise of obesity in the mid-1970s in the USA?

- How could willpower have declined in both sexes and in all age-groups simultaneously?

There are no good answers to these questions. It seems much more plausible, that (sudden and nationwide!) changes in the food environment like the US farm bills in the 1970s – which increased production, availability, and affordability of energy dense food – led to the rise of obesity.5

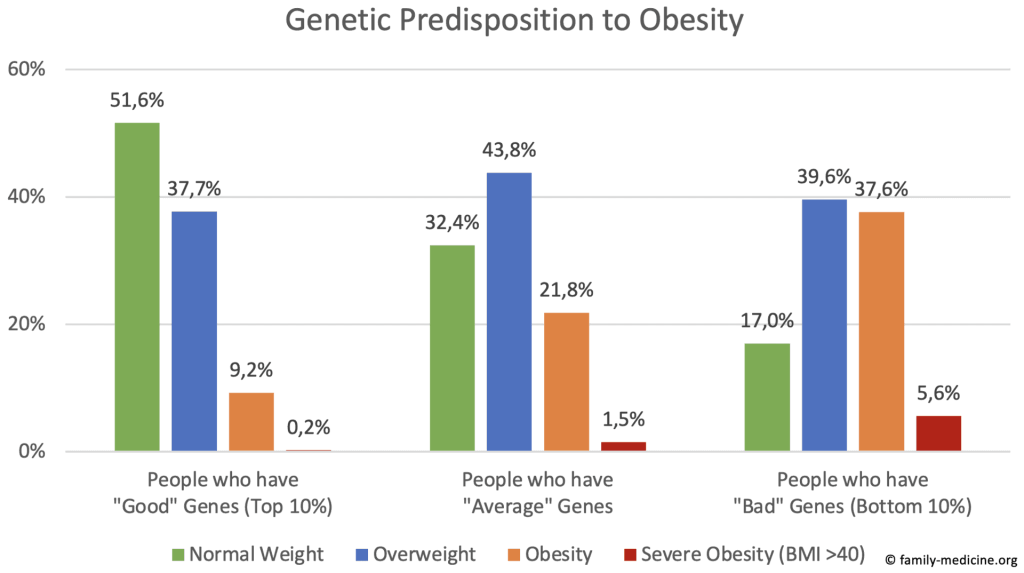

Is obesity caused by bad genes?

Well, it depends. As genes don’t change rapidly, also they cannot explain the previously mentioned rise of obesity in the USA. However, the following graph (which is crucial!) suggests that genes can largely explain why some individuals are obese and others are not:

The underlying study6 is based on 290,000 UK Biobank participants and calculated 2.1 million common gene variants. It shows that having the “worst” vs the “best” genes increased the likelihood of severe obesity 25-fold (!), of obesity 4-fold, and it increased the average weight by 13 kg. However, despite these strong associations, genes are not destiny, as 17% of those with the most disadvantageous genes still have a normal weight and most (56%) are not obese. Lifestyle is still important, but definitely not everything.

Additionally, a recent review in the journal Obesity7 concluded that even 70%-80% of weight variance might be genetic (according to twin studies, while adoption studies and nuclear family studies yielded lower values; another review8 had similar findings). Most of this genetic risk is spread over many different genes, as more than 1,100 gene loci for obesity were identified by 2020.9 However, also single genes can be important, like the FTO gene, which controls the hormone ghrelin and thereby hunger. Variants of this gene are carried by one in six European men and increase the obesity risk by 70%.10

While not about genes, here I would like to mention another cause of obesity which is also (generally) outside of our control: gut microbes. In 2023, one Nature review concluded that “we now understand that the gut microbiome profoundly impacts energy balance through diverse mechanisms”11 and another stated that “gut microbiota exert direct effects on the digestion, absorption and metabolism of food and affect body weight by modulating metabolism, appetite, bile acid metabolism, and the hormonal and immune systems”12.

In conclusion, the obesogenic environment determines the average weight of a society and thereby the “rise of obesity”, but genes and gut microbes largely determine if your weight is above or below the average. As Philip F. Smith (NIH) said beautifully, “obesity is 80% genetic and 100% environmental”. That’s key for understanding the causes of obesity.

3. How to manage obesity? Most GPs offer ineffective interventions, and neglect effective ones.

Losing weight by eating less. Or not?

If the first law of thermodynamics is still correct, then nobody can gain weight without eating more than you expend. Calories in, calories out. However, this does not necessarily mean that telling patients to “eat less and exercise more” is an effective advice for weight loss. Why not? It’s just not as logical (and neither practical nor evidence-based) as it seems…

Let’s calculate it. Someone is overweight by 20 kg. He gained this weight over the last 20 years. How much was he overeating per day on average?

- 1 kg body fat has 7,700 kcal

- 20 kg body fat have 154,000 kcal

- To gain 20 kg body fat in 20 years (7,305 days), you must overeat only 21 kcal daily!

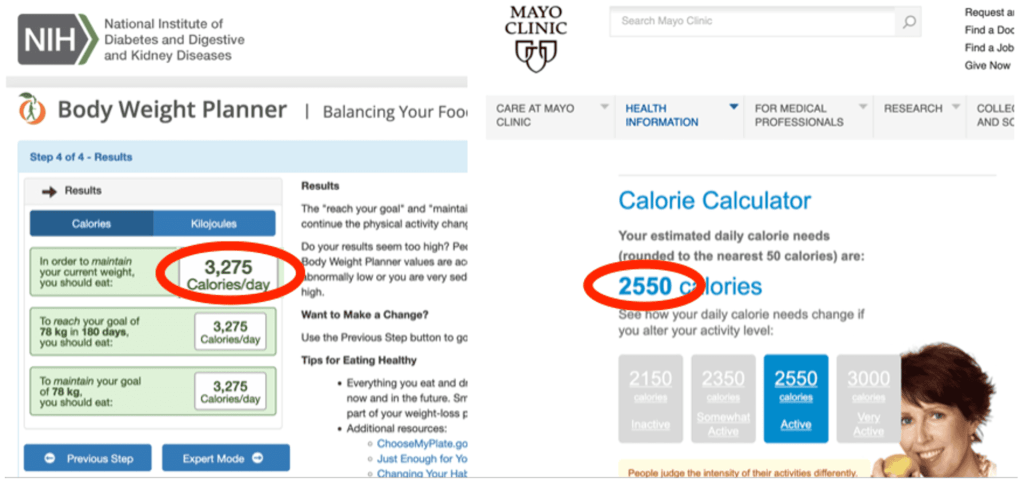

Can you estimate your today’s calorie balance with a precision of 21 kcal? Or of 210 kcal? If you cannot, then “having a negative energy balance” is not a practical approach. Also, to calculate your “energy balance”, you would need to know your energy expenditure, precisely. I put my own data into the online calorie calculators of NIH13 and Mayo Clinic14 and got quite different results (by 725 kcal per day, an imbalance which would hypothetically lead to 35 kg (!) of weight gain or loss after a year):

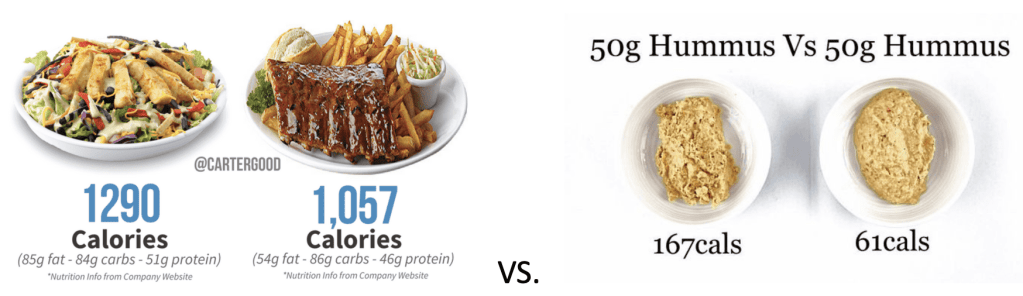

On the other side of the “energy balance” equation is your personal energy intake. Here are some comparisons, which most of us probably would have gotten wrong:

In conclusion, while you cannot gain weight without overeating, “having a negative energy balance” is not a practical advice for patients. Energy intake and expenditure estimates are both way too rough to be useful.

How to lose weight, according to the evidence?

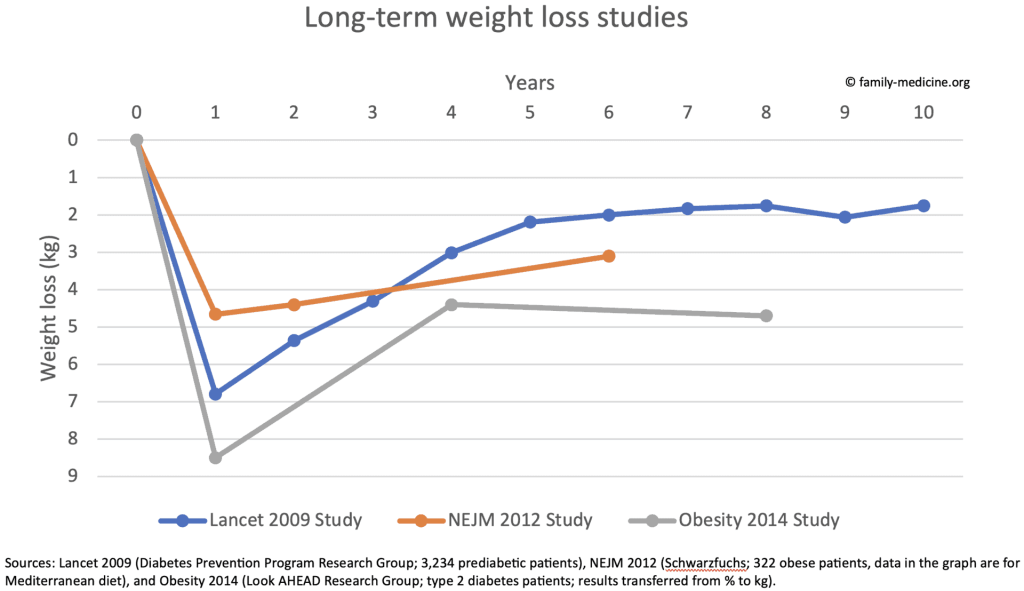

Are weight loss interventions in primary care effective? Yes, if you are satisfied with short-term results. A recent BMJ review (2022)17 included 34 trials in primary care with quite intensive interventions (each patient received a median of 12 lifestyle sessions). After one year, patients lost on average 2.3 kg, after two years a loss of 1.8 kg remained. Longer follow-up was not reported. But, as weight regain is common, what about studies on long-term maintenance? My review of the literature identified only three (!) studies with at least three-years of follow-up. If you know of another such study, please just contact me (no one did in the ten years I teach this topic). Here they are in one graph:

While these studies showed meaningful effects after one year, the weight loss after five years (2-5 kg) is modest only. Some consider these long-term effects to be clinically significant, others don’t. Nevertheless, keep in mind that these small effects were caused by highly intensive and continuous lifestyle interventions (>120 lifestyle sessions each in the Lancet study and the Obesity study), which patients usually cannot receive in real life.

However, you probably know a patient who maintained long-term weight loss. Yes, for some individuals it’s possible. The Obesity 2014 study18 showed that of those who lost ≥10% of their weight at year one, almost 40% were able to keep their weight loss of around 15% at year eight. But others even gained weight. On average, participants lost less than 5 kg.

=> If intensive weight loss interventions were a drug, they probably wouldn’t receive FDA/EMA approval (due to lack of clinically significant long-term effectiveness).

Why is long-term weight loss so difficult to achieve? One reason is hormonal regulation. One year after a weight loss, leptin, peptide YY, cholecystokinin, insulin, ghrelin, gastric inhibitory polypeptide, and pancreatic polypeptide levels are still significantly changed, which leads to increased feelings of hunger and therefore weight regain. In other words, our body strongly regulates itself to reach its target weight.19 Other reasons are that willpower is simply limited (especially in the long-term) and that genes, gut microbes, and the obesogenic environment – which all contributed to the development of obesity initially – stay unchanged and still exert their influence.

What do Guidelines on Obesity Management recommend?

A few years ago, I performed a systematic review on such evidence-based guidelines1 to answer this question. Interestingly, we found considerable agreement on how to manage overweight and obesity in primary care. Patients should join a multidisciplinary lifestyle program which includes eating less, exercising more, and changing behaviors. Pharmacological measures were recommended only additionally to a lifestyle program and bariatric surgery only if all non-surgical interventions have failed. While I am grateful to the experts who developed these comprehensive guidelines, I am skeptical it works in the long-term. Also, I believe that there is a much better approach than “eating less, exercising more” (see “conclusion” below).

What about the new weight loss drugs, GLP-1 analogs?

There is much to say! I therefore wrote a blog article about it which you can find here: Key Facts GPs Should Know About GLP-1 Analogs.

4. How harmful is obesity? Obesity is less, our attitudes are more harmful than you might think.

How harmful is obesity, actually?

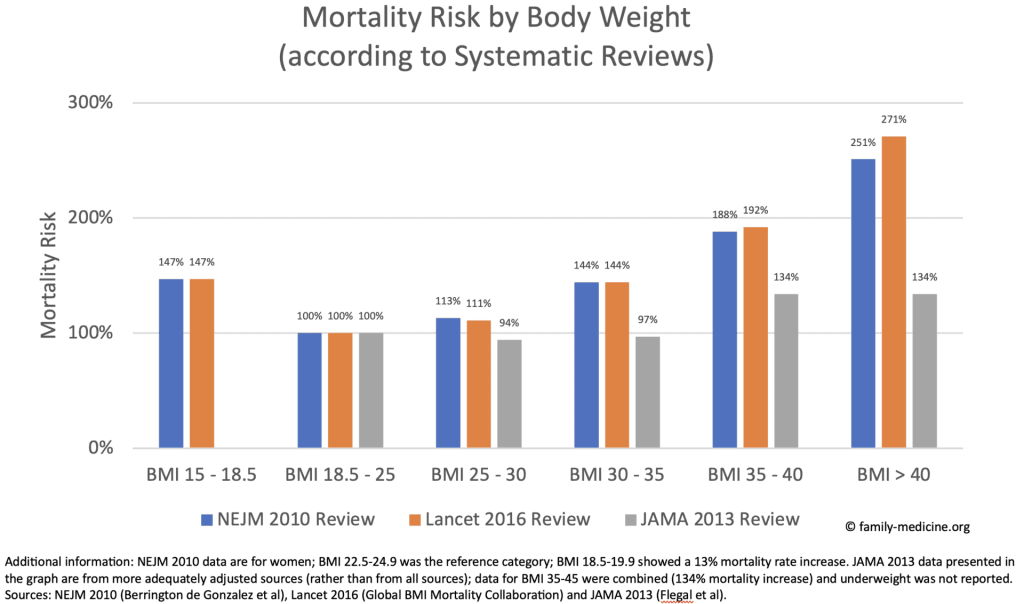

The best systematic reviews show that obesity is harmful, but probably less than you think. The graph below shows that two major reviews agree, that obesity grades 1, 2 and 3 are associated with around 45%, 90% and 160% increased mortality. However, another large review shows even a slightly reduced (!) mortality risk for overweight and obesity grade 1. What causes these differences? All reviews were performed by world leading epidemiologists, but their beliefs and decisions on how to analyze the data were just different (if you are interested in research methods, you can dive into this debate by reading the published correspondence to their articles).

How does obesity compare to smoking? Even if we disregard the more conservative estimates of the JAMA review, only the mortality rate of having a BMI>40 (+160%) is comparable to smoking ≥25 cigarettes a day (+161%, according to the 50 years observation of the British Doctors Study20, which also showed that smokers die 10 years younger, but that those who stop by age 40 gain 9 of those years back!).

How relevant is Weight Bias & Stigma?

A review concluded that ‘many healthcare providers hold strong negative attitudes and stereotypes about people with obesity’.21 Another review confirmed (while criticizing the overall quality of the evidence) an implicit and explicit weight bias.22 This may lead to poorer diagnosis and treatment and therefore to mistrust of doctors, avoidance of care and lack of adherence. Also, many obese patients internalize such attitudes and devalue themselves, which can lead to negative mental health consequences.23 I therefore agree with Partha Kar (Diabetes co-lead of NHS England), that body shaming is common but not acceptable.24

5. So, what’s my conclusion? We could be more effective, less harmful, and less frustrated.

Summary

- The rise of obesity is not caused by lack of intelligence or lack of willpower.

- The rise of obesity is (probably) caused by an obesogenic environment which promotes unhealthy foods.

- While genetics and gut microbes didn’t cause the rise of obesity either, they are a crucial risk factor for obesity (but genes are not destiny).

- While nobody can gain weight without a positive energy balance, recommending patients a negative energy balance is not a suitable or practical advice.

- Weight loss studies show that even highly intensive and continuous lifestyle interventions are only slightly effective after five years.

- Weight loss maintenance is difficult, because willpower is limited and because genes, gut microbes, and the obesogenic environment still exert their influence.

- Guidelines on Obesity Management agree on aiming for a negative energy balance as the main approach, but I disagree (based on the evidence presented above).

- Obesity is less harmful than you might think, but at least a BMI>40 is probably comparable to smoking ≥25 cigarettes a day.

- Weight bias and stigma undermines trust in doctors and harms patients physically and mentally.

What’s my conclusion?

You might think that my conclusion would be pessimistic. After all, genes are important and long-term weight loss is difficult. But quite the opposite, I’m truly optimistic, because much can be improved:

- Today, most doctors recommend their patients to “just eat less” and to “just lose weight”. It doesn’t work (and you probably know it).

- Today, most obese patients try at least once to “eat less and lose weight”. Then they regain their weight, often get disappointed and give up.

- Today, most obese patients feel ashamed of their body. Many doctors confirm this negative self-image.

- What if we follow the evidence and stop recommending an approach (negative energy balance) which doesn’t work (based on long-term studies, despite highly intensive and continuous lifestyle interventions)?

- What if we follow the evidence and start recommending a delicious Mediterranean diet, which is effective in primary25 and secondary26 cardiovascular prevention (around 30% and 26% fewer major cardiovascular events) and potentially effective against depression27? It can be recommended regardless of weight considerations, “just” to improve health and wellbeing (without leading to frustration).

- What if we follow the evidence and stop blaming patients for a condition which is considerably caused by unlucky genes and gut microbes (and not by laziness)? You might disagree, but scientific reviews7,8,11,12 support this statement.

- What if we follow the evidence and start to reverse our obesogenic environments? School buffets full of fast food and supermarkets full of cheap calories are not immutable laws of nature. ‘Making the healthy choice the easy choice’ would tackle the actual root causes of the obesity epidemic instead of just blaming obese patients.

| Bad Medicine (opinion based) | Good Medicine (evidence based) | |

| Causes | Ignoring genetics | Accepting genetics |

| Ignoring food quality | Assessing eating habits | |

| Solutions | Eat less, lose weight! | Eat healthy! |

| Attitude | Blame… | Motivation… |

My conclusion: Let’s just recommend our patients a healthy lifestyle (a Mediterranean diet and physical activity). Not in order to lose weight and to get frustrated, but to live a healthy and happy life. Also, let’s stop blaming obese patients and start changing an unhealthy food system.