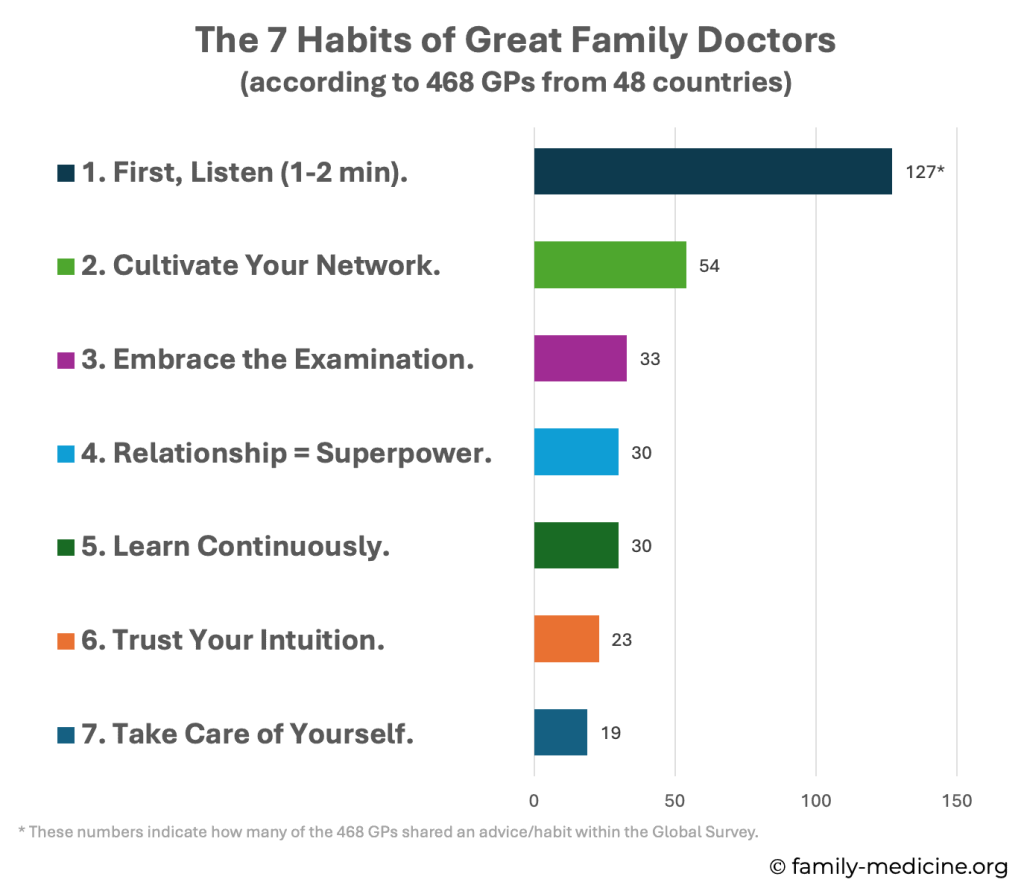

Insights from a Global Survey of 468 GPs in 48 countries

What if you could access the single best piece of advice from hundreds of experienced colleagues from around the world? We wanted to find out. We asked 468 Family Doctors across 48 countries for their most helpful wisdom and distilled their answers. The results are these seven habits of great Family Doctors – including a 4-week plan to help you integrate them into your practice starting tomorrow.

About the Global Family Medicine Community Survey | |

How? | The survey was shared via the Golden Nuggets, WONCA World and WONCA Europe newsletters. |

Who? | 468 Family Doctors from 48 countries participated anonymously. |

What? | 531 pieces of their “very best advice” were collected, analysed (rephrased, counted, and grouped thematically), and distilled into seven key habits and four additional themes. |

Table of Contents

The 7 Habits of Great Family Doctors

Four Additional Themes of Advice

The Family Medicine Challenge

Commentary from Past WONCA Presidents

The 7 Habits of Great Family Doctors

In the Global Survey, 468 GPs shared 531 pieces of advice. Many of them were shared repeatedly – here are the seven most common recommendations:

First, Listen (1-2 min)

Shared by 127 GPs. No other piece of advice was recommended that often – by far! It seems the collective wisdom is pretty sure, that improving communication skills should be our #1 priority.

Why? Early uninterrupted talk improves rapport and often reveals the diagnosis.

What did GPs recommend, precisely?

- Listen carefully. Give your patients your undivided attention. (58 GPs)

- Listen uninterruptedly. GPs recommended for 60, 90 or 120 seconds. (26 GPs)

- Ask good questions. Open-ended, ICE (ideas, concerns, expectations) or FIFE (feelings, ideas, fears, expectations). (12 GPs)

- Be curious and open-minded. Don’t jump to conclusions too early. (9 GPs)

- Trust your eyes, ears, and hands. “Good anamnesis gives you the diagnosis in 80%.” (7 GPs)

In summary, as a famous quote says: “Listen to the patient; he is telling you the diagnosis.”

Cultivate Your Network

Shared by 54 GPs. It essentially says that great Family Doctors are team players, not lonely wolves.

Why? No one knows everything. A strong network reduces insecurity, prevents tunnel vision, and simply brings joy.

What did GPs recommend, precisely?

- Build a strong personal network. Of fellow GPs, specialists, and allied health professionals. (23 GPs)

- If in doubt, ask them for advice. Make it a habit. (15 GPs)

- Find a mentor. Especially if you are young. (7 GPs)

- Nurture these relationships. Meet, call and write them regularly. Create a WhatsApp group. (2 GPs)

- Discuss your mistakes with colleagues. Everyone makes mistakes, don’t give up. (2 GPs)

- Join a Balint group. (2 GPs)

Embrace the Examination

Shared by 34 GPs. Many respondents simply wrote “examine, examine, examine”. The hands-on assessment remains a cornerstone of family medicine.

Why? Touch is diagnostically valuable, therapeutically healing, and builds trust.

What did GPs recommend, precisely?

- Always examine. Even if you think there is nothing. (25 GPs)

- Don’t be afraid to touch. Hands on! (5 GPs)

- It heals and builds trust. (3 GPs)

- Focused examination to exclude severe disease. (2 GPs)

- History is everything, examination is overrated. (1 GP)

Relationship = Superpower

Shared by 30 GPs. The big advantage of Family Medicine over other specialties, is the deep, long-term doctor-patient relationship and the trust it enables.

Why? Trust improves communication, facilitates diagnosis, strengthens placebo effects, and increases adherence. It’s the invisible medicine of general practice.

What did GPs recommend, precisely?

- Invest the time and effort to know and understand your patient deeply. (14 GPs)

- Your Superpower is your relationship and trust. (9 GPs)

- Learn about the placebo and nocebo Watch your words. (3 GPs)

- Learn about transference and counter-transference. (2 GPs)

- Never leave them. Assure your patients, that you are still their doctor, even if they don’t follow your recommendations. (1 GP)

Learn Continuously

Shared by 30 GPs. Being a good doctor is a journey without a finish line. Keep on growing!

Why? Medicine evolves constantly. Only when we stay curious and open will we evolve with it.

What did GPs recommend, precisely?

- Learning, learning, learning. (14 GPs)

- Learn from colleagues, ask them for advice. (14 GPs)

- Remain curious and open-minded. Change and learn something new. (4 GPs)

- Read good books (Ian McWhinney’s Textbook of Family Medicine and Bernard Lown’s The Lost Art of Healing) (2 GPs)

- Read the Golden Nuggets of Family Medicine 😉

Trust Your Intuition

Shared by 23 GPs. But it was difficult to put this into words. They therefore called it “intuition”, “gut feeling”, “first feeling”, “instincts”, or “something feels weird or strange”.

Why? Intuition is unconscious pattern recognition built on experience. It can defect life-threatening illness before rational evidence is available.

What did GPs recommend, precisely?

- Trust your intuition/gut, or however you might call it. (21 GPs)

- Take it seriously. If your gut feels weird, if something seems wrong, the patient might be sick. Even if you cannot explain it, if you cannot put your finger on it. (21 GPs)

- Safety net. Document your concern, arrange timely follow-up, and consider a second opinion.

Take Care of Yourself

Shared by 19 GPs. Family Medicine is meaningful, but getting sick yourself won’t help your patients. They said, “while you help others, don’t forget about yourself”.

Why? Only those who stay healthy themselves can care for others. Self-care is not egoism or luxury – it’s a professional duty.

What did GPs recommend, precisely?

- Live a healthy life. Take care of yourself. (11 GPs)

- Be kind to yourself. Forgive yourself your mistakes. You’re human too! (8 GPs)

- Take more breaks and holidays. (3 GPs)

- Accept your own limits. Protect your time and energy. (2 GPs)

Four Additional Themes of Advice

There was more advice than the seven most common habits. I clustered them into four different themes of advice.

When You Don’t Know What to Do…

Three options were shared by GPs:

Watchful Waiting (18 GPs)

- Buying time as a diagnostic tool. You don’t always need an immediate answer. (11 GPs)

- How? Rule out acute threats and consider red flags. Tell the patient what to watch for and how to seek help. Say “come back if it doesn’t get better” or make another appointment right away. (1 GP)

- Then? Use this time to consult a colleague, to read, to see how things develop. (3 GPs)

- It’s an “educated delayed care”. (1 GP)

Think Differently (14 GPs)

- Consider psychosocial causes but rule out physical explanations before. (6 GPs)

- Think again, examine again (including the basics). (3 GPs)

- Ask “What’s the patient most worried about? What’s his explanation?” (2 GPs)

- Work through differential diagnoses from common to uncommon. (1 GP)

- “If you have no clue, take a urine sample.” (1 GP)

- “If you can’t connect the issue, think connective tissues.” (1 GP)

Referral to a specialist (3 GPs)

How to Start and Finish a Consultation

The first habit said, “listen uninterruptedly for 1-2 min”. Here, seven GPs recommended to start focused and eight GPs recommended better ways to finish.

How to Start:

Prioritization of urgent and important issues early on should make the best use of the limited time. Here’s a practical tip:

- Start with “What’s your biggest concern today?” (1 GP)

How to Finish:

An evidence-based finish should uncover unaddressed issues and should improve understanding as well as memory.

- Finish with “What else do we need to discuss today?” – it often reveals something important (but it can take time…). (4 GPs)

- Give patients written instructions or leaflets for common issues. (2 GPs)

- Use the Teach-Back-Method to improve understanding and memory. (1 GP)

Leverage Modern Science and Technology

Overall, 32 GPs pointed out that science and technology can help GPs and patients.

- Apply useful technology. Specifically, ultrasound (specifically of the lung), pulse oximeter, dermatoscope, auscultation during forced expiration (wheezes or bagpipe sign), point-of-care evidence tools and AI-scribe to save time were recommended. Also, take your time to find a good vein to take blood. (9 GPs)

- Stay organized. Work systematically, keep it simple, and document properly. Also, use scores, calculators, and emergency algorithms. (9 GPs)

- Learn about pre-test probability. Because patients in family medicine have usually lower prevalences, which affects the quality of diagnostic tests. (4 GPs)

- Learn to read research studies. Be able to critically assess them. (3 GPs)

- Common things are common, rare things are rare. “When you hear hoofbeats, think horses, not zebras.” (3 GPs)

- Nurture EBM while accepting the patients approach to his/her health. (2 GPs)

- “Don’t be the first to adopt something new, and don’t be the last.” (1 GP)

Embody Family Medicine Values

Interestingly, the Global Survey also asked GPs to rate the values of family medicine. However, also this part of the survey – which asked them for advice – revealed some of the leading values.

- Be authentic and honest. Admit you don’t know everything. (18 GPs)

- Be empathic and caring. (13 GPs)

- First, do no harm. “Primum non nocere” meant doing less, examining less, referring less, and not doing everything a specialist asks for. However, it also meant learning about red flags and being “better safe than sorry”. (8 GPs)

- Be patient and stay calm. (7 GPs)

- Respect your patient. They are their own expert, even if you disagree. (5 GPs)

- Medicine should not be about money! (3 GPs)

- “Your patient is your friend.” (2 GPs)

- “Treat your patient, as if they were a family member.” (1 GP)

The Family Medicine Challenge

This article summarized the collective wisdom of 468 Family Doctors from 48 countries. This wisdom can also be translated to practical recommendations – which are learnable habits. It’s interesting to read them, but your patients only benefit when you apply them, regularly! To help you put this wisdom into practice, we’ve created the following 4-week training program. Are you ready for this challenge?

For a convenient way to track your progress, download the printable PDF version of the challenge here.

“The Family Medicine Challenge”: | ||

When? | What? | Done? |

| Week 1 | ||

| Monday | Let your first patient speak uninterruptedly for 90 seconds. | |

| Tuesday | Call one colleague for advice on a tricky case. | |

| Wednesday | Do vitals and a focused exam even if you “already know”. | |

| Thursday | Try the (quick) Teach-Back method to improve understanding. | |

| Friday | Make a 15-min debrief with a trustworthy colleague. | |

| Weekend | Do a physical activity (what do you enjoy most?). | |

| Week 2 | ||

| Monday | Learn the background and life story of one quite new patient. | |

| Tuesday | Write down a list of go-to colleagues. Reconnect with one. | |

| Wednesday | Start a WhatsApp group and invite interested colleagues. | |

| Thursday | Offer one patient a written plan of your instructions. | |

| Friday | Make a debrief and share a mistake (if you expect kindness). | |

| Weekend | Do something relaxing (maybe meditation, yoga or sauna?). | |

| Week 3 | ||

| Monday | End a consultation with “what else should we discuss today?” | |

| Tuesday | Write down a list of great questions. Ask one of them today. | |

| Wednesday | Find a local Balint group and join it once. | |

| Thursday | Ask a potential Mentor to meet for a coffee. | |

| Friday | Make a debrief and discuss cases of following your intuition. | |

| Weekend | Just meet with a good friend who makes you feel well. | |

| Week 4 | ||

| Monday | Add one more break to your schedule (no digital distraction). | |

| Tuesday | Read about placebo/nocebo effects. Plan to use/avoid them. | |

| Wednesday | Read about pre-test probability and its diagnostic effects. | |

| Thursday | Order a good, inspiring book about medicine. | |

| Friday | Make a debrief and discuss what you learned this week. | |

| Weekend | Plan your next, longer vacation. | |

Additional Information:

- Each Friday includes a “debrief”. It’s a short, reflective conversation with a trusted colleague about the week’s challenges. This should help your progress and keep you motivated.

- You might be more committed and engaged, if you do this entire challenge (and the debriefs) together with colleagues.

- Afterwards, ask yourself these questions to reflect:

- Which of these habits did you already apply regularly? Cross them out.

- Which of these habits would be important for you to start? Highlight them.

- What could you do to apply them regularly? Write down your plan.

Are you ready?

I hope you found this survey and article useful. I would like to finish it by citing one GP from the Global Survey:

“Every time a patient enters your office, it is a sacred moment – one that calls for mindfulness and care… in that moment, we are there to serve – with quality, safety, and compassion.”

Found this article helpful?

Share it with colleagues who could benefit too!

Commentary from Past WONCA Presidents

Thank you so much for taking the time to comment on my blog post. I truly appreciate your kind words and the thoughtful, scientific reflections you shared. Your insights add real depth to the discussion and are very encouraging for me and, I am sure, for the readers as well. It’s an honor to benefit from your expertise.

Dr Anna Stavdal

WONCA Past President 2023-2024

Prof Richard Roberts

WONCA Past President 2010-2013

Prof Chris van Weel

WONCA Past President 2007-2010

The values and principles of family medicine constitute the foundation of our discipline. Societal trends are always reflected in health systems, and first of all in primary care. Change is a continous process. To maintain and develop the foundation of family medicine, it is necessary to reflect continously on the values and principles of our profession. That enables us to adapt to change without losing sight of our values and working method.

This survey gives an idea of how family doctors globally work to maintain and develop their professional identity. The form of «advices» and description of «habits», make the outcome of the survey accessible and useful for primary care professionals at all steps in their professional career.

The format lives up to an old wise saying: «Man needs more to be reminded, than instructed».

Thank you to Florian for his «Golden Nuggets» and for carrying out this survey.

My commentary consists of two parts: the specific habits and themes that were identified and the potential scientific impact of the survey. I aimed to write my commentary in the style of a review for a research paper.

The 7 habits described seem reasonable. The advice with the most responses (127) was to invite the patient to share their history without interruption. Mere listening is not enough. Active listening requires sitting in an open position, making eye contact, and resisting distractions like screens. I agree that relationships can be a superpower for family doctors by helping build trust and improve patient and professional satisfaction. Yet, most patients are seen only a few times by any one doctor. We need more skill in optimizing therapeutic relationships at every visit with every patient. Several of the habits focus on ways to arrive at a correct diagnosis. Yet, only about 1 in 4 consultations involve a new problem. The bigger challenge today is to develop skills in helping people make necessary lifestyle changes and manage chronic conditions. Continuous learning is a key habit for any professional. I was surprised that none of the respondents apparently advised learning critical appraisal skills (e.g., POEMs vs DOES) or anticipated the changing learning environment with the advent of artificial intelligence (AI).

The 4 themes are difficult to challenge, although I would suggest an opening phrase other than,

“What’s your biggest concern today?” This suggests that every visit involves a concern or problem. So many visits today may have been requested by the doctor for preventive services or administrative purposes that the patient may not feel that they have a concern or problem. Better is something more general such as “What would you like to discuss today?” or “How may I help today?”

The article appropriately notes the challenges of putting these bits of advice into practice. I believe that the strategies and tools of Human Factors Science will become more widely known and used, as they appear to offer the best approach to meaningful and sustained change. The quality movement has also provided examples of approaches to quality improvement that have been helpful in primary care, such as quality circles, practice tutors, audit, case reviews by the care team, and so on.

Like most research studies, it raises more questions than it answers. What advice would patients or physician staff give to their family doctors? What attributes or behaviors do health system leaders seek in family doctors? Finally, even the most frequent advice given (“listen to the patient”) was cited by only 1 out of 4 respondents (127 out of 468). How did the other 3 out of 4 respondents feel about that piece of advice, or any other advice for that matter? These additional questions can be answered through an expanded study design that combines qualitative and quantitative data using mixed methods (focus groups, individual interviews, semi-structured surveys for patients, physicians, staff and leaders, etc.).

It makes an interesting read to see how an international group of family physicians view their discipline – and experience the competences required to perform their professionalism.

Reassuring is that family physicians from different countries, working under different health systems and facing different socio-economic and cultural conditions share such a broad common ground. It emphasizes that family medicine, primary care, is an international discipline, bound by common core values in caring for patients and communities.

That, in my view, is a positive side that can not treasured enough: too often academics, policymakers and educators assume that family physicians, primary care, present just a local addition to an otherwise ‘universal’ healthcare. The opposite is true: we share values and competencies over national borders, irrespective of the rules and regulations of the health systems imposed upon us. This is the unfathomed power of family medicine, a power to rely on in international collaboration to improve the health of populations.

But the paper deserves some critical reflection as well. First, it is in the presentation of number of respondents who supported key components of our discipline. The danger is that this may lead to a quantitative valuing, in which the items drawing the largest support are seen as the most important. As I see it, all are important, and their importance is in applying them in coherence, connected to the needs of patients and populations. This need of applying interconnected measures underscores the complexity of family medicine, in caring for all patients, with unselected health problems. Again something that can not be stressed this strong enough or we would give way to the view that primary care is just a ‘simple’ field of practice.

And related to this: we tend to describe our work in broad terms using big words – like empathy or intuition – without problematize what is behind it. Empathy is an important value in connecting to patients and communities. But under what conditions will it be beneficial? Intuition is important but how does it work? Unless we are able to dig into their true meaning big words may remain empty boxes – to the detriment of the most important discipline in the health system.